A Sensory Exploration of Taste, Aroma and Flavour

In Joey's second article, he dives deeper into the difference between 'Taste & Flavour'

23 August 2022 · 9 min read

TASTE + AROMA = FLAVOUR

In my first article (if you’ve not seen it yet, go back and give it a read), I introduced the theory that cocktails are one of the few actual multi-sensory forms of art and that we should employ an artistic approach to their teaching and learning process; focusing first on the understanding of taste and flavour. Everything can affect our enjoyment of cocktails, from how they look when they’re placed in front of us to the music playing, but we can all agree that the most important factor in whether we like a cocktail is how it tastes. To master the art of flavour creation, we must fully understand taste and flavour and how our bodies and minds process them.

Taste vs Flavour - Same, Same, but Different

We first need to establish the difference between taste and flavour. While the words are interchangeable in the English language (and I have and will use them interchangeably throughout these articles, sorry for any confusion), they have two distinct meanings.

A Matter of Taste

Let’s start with taste. Taste refers specifically to the five things we can physically sense through the taste receptors on our tongues, in our mouths and, believe it or not, in our stomachs. These are: sweet, sour, bitter, salt and this funny thing we call ‘umami’ – sometimes referred to as ‘savoury’ and collectively referred to as ‘taste elements’. Our bodies evolved to pick out these five elements specifically, as they identify the presence of compounds and molecules that are either crucial to the smooth running of our bodies, or potentially harmful to us. Effectively, they tell us if something is good to eat or should be avoided at all costs. Let’s look at the role each one plays.

The Taste Elements

Sweetness is a sign of energy-giving carbohydrates or sugars in food. The most common sugar our body uses is glucose, our primary energy source, and we would be dead without it. For this reason, our clever bodies have evolved to release endorphins (the ‘feel-good chemical’) when we consume anything sweet.

Saltiness indicates electrolytes, the main ones being potassium, sodium, and chloride. Electrolytes are essentially electrically charged minerals that help our body with its critical functions by carrying electrical impulses around the body to program energy production and muscle contraction – pretty damn important when you consider our heart is a muscle that needs to contract to beat.

Sourness signifies the presence of critical vitamins and some antioxidants. Still, it serves the dual purpose of letting us know if something is not ripe and ready to be eaten or if something is rotting and being avoided.

Bitterness can warn us of harmful toxins in food. We detect bitterness at the lowest threshold of any of the taste elements. However, our bodies learn to tolerate and often appreciate this sense as we grow older or have positive experiences with it.

Umami is the most recently defined and probably the most difficult to describe of the taste elements. It wasn’t until 2002 when umami taste receptors were discovered in the human body, that it was defined as a taste element. Umami shows the presence of glutamates – healthy amino acid compounds which are the building blocks of protein – key to the construction and repair of our bones and muscles. These are found in all sorts of food, from red meat to tomatoes, so pinning them down is the most challenging.

Like our other senses – sight, touch, smell and hearing – this sense operates on a subconscious level. We do not think we need these elements, but our body manifests this desire through cravings. But this is not where the importance of taste elements stops when it comes to cocktails, they also play a crucial role in flavour creation.

Flavour - It's all in the Mind

Flavour is our brain’s response when different taste elements are combined with aroma molecules in their most accurate form. Our clever minds create a mental pathway from that flavour to the word for what we’re consuming. But really, it’s much more complex and exciting than that. In contrast, the taste is a response of an individual sense that happens in the subconscious. Instinctually, the flavour results from our minds working in harmony and is constructed entirely in our brains. While taste is hardwired, something we are all born with, flavour is learned through our experiences with the natural world, meaning that while the taste is universal, the flavour is unique to each of us.

Lock & Key

Aroma is by far the essential sense regarding flavour, hence why if you’ve got a bad cold and a blocked nose, you can lose the ability to perceive taste entirely. But what are aromas? It is essential to make it clear that everything in the world (and in the universe) has an aroma, as aromas are just volatile molecules being omitted from a structure, be that solid, liquid or gas. Whether we can smell them depends on how volatile they are – how many molecules they release – and if we have the right aroma receptors in our bodies to process them. Think of aroma receptors and aroma molecules like a lock and key; if the molecule fits in the receptor, boom, you can smell it; if it doesn’t work, it’s a no-go.

Man vs Dog

I always ask bartenders when I’m training: “who has a better sense of smell, me or my dog, Maurice?” Without fail, every single one of them will vote for Maurice, and who can blame them? Just look at that nose! But the answer is not as simple as that; it depends on which sense of smell we’re talking about.

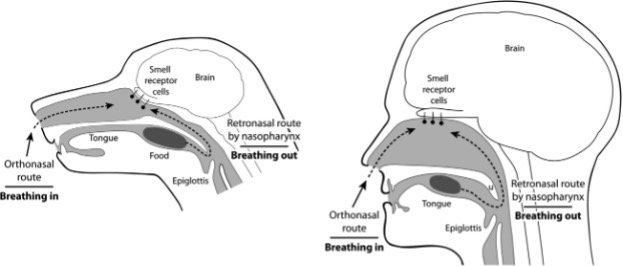

Orthonasal - The Sniffing Smell

We ‘smell’ things in two distinct ways. The first, and the immediate one we think of, is called ‘orthonasal’ – sometimes called the ‘sniffing smell’ – and refers to everything we smell in the outside world. We developed this smell to trigger emotional responses to aromas in our immediate environment. So, if you could smell smoke that was a warning of fire close by, or similarly if you could smell the pheromones from another human that could give an indication of whether they were aggressive or amorous. These aroma molecules pass up through or nasal canal to our olfactory bulb (the part of the brain responsible for all things aroma) where they are processed into recognised scents. As we evolved, and our conscious mind began to make decisions over our instincts, our need for this sense decreased, as did its sensitivity. When it comes to this sense of smell, Maurice wins every time as he has somewhere between 10,000 to 100,000 more scent receptors on is nasal canal than I do, meaning he can detect far more aromas, at a far lower concentration and further distance that I could ever dream of. 1-0 to the hound.

Retronasal - Breathing Out

The second way we smell is called ‘retronasal’, which occurs when we consume something, be that food or drink, and breathe out. As we breathe, the aroma molecules from what we are consuming pass out through the back of our nose through the nasal cavity and into our brains. From there, our brain processes these aromas and paints a mental picture of what that aroma is. When we compare the anatomies of the human versus the dog, we can see that they are very different and designed for other purposes. The dog takes most of its information about the world around it through its nose, constantly sniffing everything on the ground below it. Humans, however, have learned to walk on two feet, far above the ground, and developed keener eyesight to process the information of their world, hence the lessened capacity for orthonasal smelling. But if we look at the nasal cavity, we can see that humans is far larger, and this is again down to evolution. As we spread out across the world, our diet divulged, and as omnivorous hunter-gatherers, we would eat a far more varied diet than our carnivorous canine friends. So, we would need to process far more information about what we were eating, rather than what we were smelling. We are especially good at processing combinations of aroma molecules retronasally, with a conservative estimate suggestion, there are over 1 trillion different combinations we can detect. That makes it 1-1 in the battle of man versus dog.

What about our Other Senses?

I mentioned before that flavour is constructed by all our senses working harmoniously. The reality is that while sight, touch, sound and especially expectation play a crucial role in flavour, they are all responsible for how much we enjoy a flavour, rather than the creation of the flavour itself. For a flavour to be fully maximised, it requires the perfect balance of all these elements and, of course, the perfect balance of tastes, and we’ll get into all of that and much more in the following article.

———— The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Freepour.